임피 (군사)

package.lua 80번째 줄에서 Lua 오류: module 'Module:Namespace detect/data' not found. 스크립트 오류: "Unsubst" 모듈이 없습니다. package.lua 80번째 줄에서 Lua 오류: module 'Module:Message box/localize' not found.

임피 는 '전쟁'이나, '전투'를 의미하는 줄루어 단어이며, 전쟁을 위해서 협회를 통해 모인 모든 사람의 단체이다. 예를 들어 '임피 야 마쇼샤'(impi ya mashosha)는 '군대'를 나타내는 용어이다. 그러나 영어에서의 임피는 종종 줄루족의 군사 연대를 지칭하는 데 사용되기도 한다. 사실 이들은 줄루어로 이부토(ibutho)라고 불리운다. 임피는 역사적으로, 부족 전쟁 관습에서는 멀리 떨어져 있었다. 그때 무장한 상태로 전장에서 활약했던 사람들을 임피라고 불렀다. 그들은 센잔가코나 카자마의 의해 추방된 아들인 줄루족의 왕 샤카에 의해 급진적으로 체계화되었다. 샤카는 센장가코나 카자마 (Senzangakhona kaJama) 왕에게서 추방당한 사생아였지만, 1817~1819년 은드완드웨 (Ndwandwe)-줄루 전쟁에서, 므테스와 (Mthethwa)의 국왕 딩기스와요 (Dingiswayo)의 군대의 장군으로서 탁월한 기량을 보여 주었다.

기원[편집]

줄루족의 임피는 남부 아프리카 지역에 도착해 번성하기 전에 상대적으로 작은 줄루 부족의 통치자인 샤카 (Shaka)의 으로 널리 알려져 있지만 일부 역사가들의 주장으로는 부족을 이끄는 족장으로서 가장 초기 형태는 므테스와 지역의 족장 딩기스와요 (Dingiswayo) 의 혁신에 있다고 한다. (Morris 1965). [2] 이러한 혁신은 이응탕가(iNtanga) 와 같은 기존의 부족 관습을 바탕으로 이루어지게 되었다. 이것은 대륙 남부 지역의 많은 반투족 사람들에게 공통적인 연령 등급의 전통이었다. 청소년들은 각각 문화를 공유하는 집단에서 연령 그룹으로 구성되었다. 특정한 의무와 부족 의식을 담당하는 집단이었다. 고학년 학생들은 소년부터 본격적인 성인 및 전사인 우쿠부트브와 (ukuButbwa)로의 성장을 알리는 상담, 임무 그리고 성년이라는 것을 알리는 유도 행사를 위해 주기적으로 부족장 kraal 또는 인두나스 (inDunas) 에게 불려졌었다. 크랄(Kraal) 혹은 합의 장로 (Settlement elders)는 일반적으로 지역의 분쟁 및 문제를 처리했다. 크랄의 위에는 인두나스가 있었고, 인두나스 위에는 특정 부족이나 혈통의 족장이 있었다. 인두나스들은 분쟁 해결에서 세금 징수에 이르기까지, 자신의 족장에 대한 행정 문제를 처리했다. 전쟁 당시, 인두나스들은 해당 지역의 전투원들을 지휘하였고 전투에 배치된 군대의 지도력을 형성하였다. 인두나스들의 지도 하에, 연령 등급인 이응탕가는 전 세계적으로 임피라고 알려질 체계적인 연대 조직의 기초를 형성하게 되었다. [3]

초기 부족 전쟁의 제한된 특성[편집]

군사전은 샤카가 떠오르기 전 동안 반투족 사이에서도 약하게 일어났지만 주기적으로 일어났다. 목표는 일반적으로 소를 도둑질하는 것과 개인적인 모욕에 대한 복수, 혹은 방목지와 같은 지역의 영토 분쟁 해결과 같은 종류로 제한되었다. 일반적으로 임피 라고 불리우는 느슨한 폭도들은 그들의 난투에 참가하였다. 패잔병에 대한 몰살 운동은 없었다. 그들은 간단히 펠트의 다른 공공 지대로 옮겨갔고, 균형을 되찾았다. 활과 화살이 많이 알려져 있지만, 잘 사용되지는 않았다. 숙련된 창병과 추적자에게 의존했던 전쟁은 마치 '사냥'과도 같았다. 기본 화기는 투창 용도인 얇은 6 피트짜리 창이었다. 몇몇은 전투에 투입되기도 했다. 방어 무장은 샤카 이후 향상된 작은 소가죽 방패를 포함했다. 많은 전투는 부족 전사들이 지정된 시간과 장소에 만나는 전략 등이 계획되어 있었고, 그 동안 부족의 여성들과 아이들은 먼 거리에서 이 축제를 지켜보기도 했다. 의례적인 조롱, 단 한번의 전투와 잠정적인 요금이 전형적인 흐름이었다. 만약 사건이 이전에 사라지지 않았다면, 한쪽이 적들을 몰아내면서 지속적인 공격을 할 수 있는 충분한 용기를 찾을 수 있을 것이다. 사상자는 보통 매우 적었다. 패배한 부족들은 땅이나 소에 돈을 주고 사로잡힌 인질들을 통해 소를 사용할 수 있었지만 몰살이나 대량 인명 피해는 극히 드물었다. 전술은 기본적이었다. 의례적인 전투 외에는 기습이 가장 흔한 전투 방식이었는데 이는 크랄의 자리를 갈망하거나, 포로 노획하거나, 소 떼를 움직이게 하는 것으로 특징지어졌다. 목회자와 경농주의자였던 반투족들은 보통 적을 물리칠 수 있는 영구적인 방어 시설을 짓지 못했다. 위협을 받고 있는 부족들은 그들의 미약한 물질적 소유물들을 간단히 챙기고 그들의 소들을 몰면서, 약탈자들이 사라질 때 까지 도망갔다. 만약 약탈자들이 그들을 방목 구역에서 영구적으로 추방하지 않았더라면, 도망가는 부족들은 하루 이틀 안에 재건하려고 돌아오게 될 것이었다. 따라서, 줄루 임피의 창설은 유럽인들의 침략이나 샤카 시대가 오기 훨씬 전에 존재했던 부족 구조에 존재한다.

딩기스와요의 부상[편집]

19세기 초, 여러가지 요인의 조합이 풍습 규칙을 바꾸기 시작했다. 이것은 백인 정착자들의 인구 증가와 성장이 포함되었다. 그리고 재산을 몰수당한 케이프와 포르투갈, 모잠비크 원주민 노예들과 야심적인 "뉴맨"이 급부상했다. 그러한 전사들을 "딩기스와요" (Dingiswayo, 문제아)라고 불려졌다. 므테스와는 딩기스와요로 유명세를 떨쳤다. 도널드 모리스와 같은 역사가들은 그의 정치적 재능이 비교적 가벼운 패권의 기반이 된 것을 보여준다고 주장한다. 이것은 이것은 외교와 정복의 결합을 통해, 상대를 말살하거나 노예제도를 통해서가 아니라 전략적인 관계개선과 무기의 현명한 사용을 통해 성립되었다고 인정받았다. 이러한 권력은 므테스와의 영향권에 있는 작은 부족들의 잦은 불화와 싸움을 줄이게 되었고 그들의 힘을 조금 더 중앙집권화된 세력에게 전달하였다. 딩기스와요의 아래에서 연령 등급은 병역 기피로 간주되었다. 그래서 새로운 질서를 유지하기 위해 더 자주 배치되었다. 샤카가 꽃피게 된 것은 엘랑에니 (en:eLangeni)와 줄루를 포함한 작은 부족들로부터였다.

샤카의 즉위와 혁신[편집]

샤카는 자신이 딩기스와요의 가장 유능한 전사 중 한 명이라는 것을 증명했다. 그의 나이 또래의 군대를 소집한 후 므테스와 군대에서 복무하였다. 초기에는 어디서 배속되든 자신의 이지크웨 (iziCwe) 연대와 싸웠으나, 처음부터 샤카의 전투 접근법이 전통적 틀에 맞지 않는다는 한계에 다다랐다. 그는 자신만의 방법과 방식을 만들기 시작했다. 더 크고, 단단한 방패와 유명한 짧은 찌르기 창인 이클와 (iKlwa)를 설계했고 걸어다니는 속도를 늦추는 것으로 추정되게 하는 소가죽제 샌들을 폐기했다. 이러한 방법들은 소규모의 효과가 있는 것으로 증명되었지만 샤카 자신은 그의 부하에 의해 제지당했다. 그의 전쟁에 관한 개념은 딩기스와요의 화해 방법보다 몹시 극단적이었다. 그는 사상자가 비교적 가벼운 각각의 챔피언들의 결투, 산발적인 습격, 한정된 교전과는 달리 신속하고 살벌한 결정을 내리려고 노력했다. 그의 멘토이자 부하인 딩기스와요가 생존해 있는 동안 샤카의 방법이 재조명되었지만, 이 점검으로 줄루 족장에게 훨씬 더 넓은 활동범위가 주어졌다. 훨씬 더 엄격한 형태의 부족 전쟁이 일어난 것은 그의 통치하에 있었다. 훨씬 더 엄격한 형태의 부족 전쟁이 일어난 것은 그의 통치하에 있었다. 이 새로운 초점은 무기, 조직, 전술의 변화를 요구했다.

무기와 방어구[편집]

샤카는 전통 무기의 새로운 변종을 도입한 공로를 인정받고 있다. 길고 가느다란 창을 줄였고 짧은 칼날로 찌르는 창을 선호하게 되었다. 또한 더 크고 무거운 소 가죽 방패 "이시흘랑구"(isihlangu)를 도입했으며, 보다 효과적인 백병전에서 적들에게 더 효과적으로 가까이 갈 수 있도록 군대를 훈련시켰다. 던지는 창은 폐기되지 않았고 찌르는 도구처럼 표준화되어 일반적으로 가까이 접촉하기 전에 적에게 퇴역되었다. 밀착 된 접촉 전에 미사일 무기처럼 운반되었다. 이러한 무기 변화는 공격적인 이동성과 전술적 조직과 통일되도록 촉진되었다.[3]

무기처럼, 줄루 전사들은 찌르는 창인 이클와(iKlwa)를 들고 있었다. (이를 잃어버리게 된다면 처형당했다.) 주로 크놉케리에(Knobkerrie) 라고 불리던 곤봉인 줄루어로는 이위사(iwisa)로 알려진 커다란 활엽수로 만들어진 둔기가 유행했고 줄루 장교들은 종종 반달 모양의 줄루 도끼를 들고 다녔는데 이 무기는 그들의 계급을 나타내는 상징물이 되었다. 이클와는 (사람의 몸에서 빼낼 때 나는 소리 때문에 이와 같은 이름이 붙었다.) 스크립트 오류: "convert" 모듈이 없습니다. 길이의 넓은 칼날은 샤카의 발명품으로, 이전에 사용되었던 투창 이파파(ipapa)를 대체했다.( 공중으로 날아갈 때 "파 파" 하는 소리가 들리기 때문이라고 한다). 이론적으로 이파파는 근접 무기와 투척 무기로 사용될 수 있지만, 샤카 시대에는 전사들이 무기를 던지는 것이 금지되어있어 무장을 해제하고 상대방에게 다시 되돌릴 수있는 물건을 줄 수 있었을 것이다. 더욱이 샤카는 전사들에게 백병전에 돌입시키는 것을 좌절시킨다고 생각하였다.

샤카의 동생이자 후계자인 딩가네 카젠자코나(Dingane kaSenzangakhona)는 투척 창의 사용을 보어인들의 총기에 대항하기 위해 다시 도입한 것으로 추정된다.

물자[편집]

다른 군대와 마찬가지로, 빠르게 움직이는 무리에는 보급품이 필요했다. 보급품은 군대에 붙어 보급품, 요리 냄비, 수면용 매트, 여분의 무기와 다른 재료 등을 운반하는 소년들에 의해 제공되었다. 소는 가끔씩 살아있는 식량 저장소로 사용되기도 했다. 지역적 맥락에서의 이러한 준비는 그리 특이한 상황이 아니었을 것이다. 또 다른 점은 체계화와 조직화였는데, 이것은 줄루가 급습 임무에 파견되었을 때 주요한 이익을 가져다 주는 패턴이었다.

연령 등급(Age-grade) 연대 체계[편집]

Age-grade groupings of various sorts were common in the Bantu tribal culture of the day, and indeed are still important in much of Africa. Age grades were responsible for a variety of activities, from guarding the camp, to cattle herding, to certain rituals and ceremonies. It was customary in Zulu culture for young men to provide limited service to their local chiefs until they were married and recognised as official householders. Shaka manipulated this system, transferring the customary service period from the regional clan leaders to himself, strengthening his personal hegemony. Such groupings on the basis of age, did not constitute a permanent, paid military in the modern Western sense, nevertheless they did provide a stable basis for sustained armed mobilisation, much more so than ad hoc tribal levies or war parties.

Shaka organised the various age grades into regiments, and quartered them in special military kraals, with each regiment having its own distinctive names and insignia. Some historians argue that the large military establishment was a drain on the Zulu economy and necessitated continual raiding and expansion. This may be true since large numbers of the society's men were isolated from normal occupations, but whatever the resource impact, the regimental system clearly built on existing tribal cultural elements that could be adapted and shaped to fit an expansionist agenda.

After their 20th birthdays, young men would be sorted into formal ibutho (plural amabutho) or regiments. They would build their i=handa (often referred to as a 'homestead', as it was basically a stockaded group of huts surrounding a corral for cattle), their gathering place when summoned for active service. Active service continued until a man married, a privilege only the king bestowed. The amabutho were recruited on the basis of age rather than regional or tribal origin. The reason for this was to enhance the centralised power of the Zulu king at the expense of clan and tribal leaders. They swore loyalty to the king of the Zulu nation.

다양한 종류의 연령 등급 그룹은 당시 반투족 문화에서 흔했으며, 실제로 아프리카의 많은 부족들에게서 여전히 중요한 문화이다. 연령 등급캠프를 지키는 것부터 가축 떼기, 특정 의식 및 의식에 이르기까지 다양한 활동을 담당했다. 줄루 문화에서는 젊은이들이 결혼하여 공식적으로 가장으로 인정받을 때까지 지역 추장에게 제한된 봉사를 제공하는 것이 관례였다. 샤카는 이 시스템을 조작하여 지역 클랜 지도자의 관습적인 복무 기간을 자신에게 이전하여 개인 권력을 강화했다. 나이를 기준으로 한 이러한 그룹은 현대 서구의 의미에서 영구적 인 유급 군대를 구성하지는 않았지만, 임시 부족 부담금이나 전쟁 집단보다 훨씬 더 많은 지속적인 무장 동원을 위한 안정적인 기반을 제공했다.

샤카는 다양한 연령 등급을 연대로 구성하고 특수 군사 크랄로 분류했으며 각 연대는 고유 한 이름과 휘장을 가지고 있다. 일부 역사가들은 대규모 군사 시설이 줄루 사회의 경제적 낭비였으며 지속적인 공격과 확장이 필요했다고 주장한다. 많은 수의 사회 남성이 정상적인 직업에서 격리 되었기 때문에 사실일 수 있지만, 자원에 미치는 영향이 어떻든간에 연대 체제는 확장주의 의제에 맞게 조정되고 형성 될 수있는 기존 부족 문화 요소에 분명히 구축되었다.

20번째 생일이 지나면 젊은이들은 공식적인 이부토(Ibuto) (복수형 "아마부토"amabutho) 또는 연대로 분류된다. 그들은 활동적인 봉사를 위해 소환 될 때 그들의 집결 장소 인 i = handa (기본적으로 가축을 위한 목장을 둘러싸고 있는 비축된 오두막 집단이기 때문에 종종 '홈스테드'라고 함)을 지었다. 한 남자가 결혼 할 때까지 적극적인 봉사는 계속되었고 왕만이 부여한 특권이었다. 아마부토는 지역이나 부족 출신이 아닌 나이를 기준으로 모집되었다. 그 이유는 씨족과 부족 지도자를 희생시키면서 줄루 왕의 중앙 집중식 권력을 강화하기 위함이었다. 그들은 줄루 국가의 왕에게 충성을 맹세했다.

Mobility, training and insignia[편집]

Shaka discarded sandals to enable his warriors to run faster. Initially the move was unpopular, but those who objected were simply killed, a practice that quickly concentrated the minds of remaining personnel. Zulu tradition indicates that Shaka hardened the feet of his troops by having them stamp thorny tree and bush branches flat. Shaka drilled his troops frequently, implementing forced marches covering more than fifty miles a day.[4] He also drilled the troops to carry out encirclement tactics (see below). Such mobility gave the Zulu a significant impact in their local region and beyond. Upkeep of the regimental system and training seems to have continued after Shaka's death, although Zulu defeats by the Boers, and growing encroachment by British colonists, sharply curtailed raiding operations prior to the War of 1879. Morris (1965, 1982) records one such mission under King Mpande to give green warriors of the uThulwana regiment experience: a raid into Swaziland, dubbed "Fund' uThulwana" by the Zulu, or "Teach the uThulwana".

Impi warriors were trained as early as age six, joining the army as udibi porters at first, being enrolled into same-age groups (intanga). Until they were buta'd, Zulu boys accompanied their fathers and brothers on campaign as servants. Eventually, they would go to the nearest ikhanda to kleza (literally, "to drink directly from the udder"), at which time the boys would become inkwebane, cadets. They would spend their time training until they were formally enlisted by the king. They would challenge each other to stick fights, which had to be accepted on pain of dishonor.

In Shaka's day, warriors often wore elaborate plumes and cow tail regalia in battle, but by the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, many warriors wore only a loin cloth and a minimal form of headdress. The later period Zulu soldier went into battle relatively simply dressed, painting his upper body and face with chalk and red ochre, despite the popular conception of elaborately panoplied warriors. Each ibutho had a singular arrangement of headdress and other adornments, so that the Zulu army could be said to have had regimental uniforms; latterly the 'full-dress' was only worn on festive occasions. The men of senior regiments would wear, in addition to their other headdress, the head-ring (isicoco) denoting their married state. A gradation of shield colour was found, junior regiments having largely dark shields the more senior ones having shields with more light colouring; Shaka's personal regiment Fasimba (The Haze) having white shields with only a small patch of darker colour. This shield uniformity was facilitated by the custom of separating the king's cattle into herds based on their coat colours.

Certain adornments were awarded to individual warriors for conspicuous courage in action; these included a type of heavy brass arm-ring (ingxotha) and an intricate necklace composed of interlocking wooden pegs (iziqu).

전술[편집]

package.lua 80번째 줄에서 Lua 오류: module 'Module:Message box/localize' not found.

위 사진의 1번은 적의 위치, 2번은 뿔 부위, 3번은 흉부, 4번은 허리를 나타낸다.

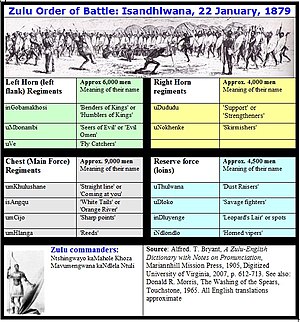

줄루족은 일반적으로 잘 알려진 "황소의 뿔"(package.lua 80번째 줄에서 Lua 오류: module 'Module:Langname/data' not found.: impondo zenkomo) 대형을 만들어 공세를 유지했다. 황소의 뿔은 다음 세 가지 부분으로 나눌 수 있다.

- "뿔 부위" 라고 불리는 좌측과 우측의 측면 부분 의 군사들은 뿔 모양으로 적을 둘러싸 꼼짝 못하게 했다. 보통 뿔 역할을 하는 군인들은 젊고 파릇파릇한 전투원들로 구성되어 있었다.

- "흉부", 가끔씩 "머리" 라고 불리는 중앙의 주 병력들은 적들에게 치명적인 일격을 안겨줬다. 기초적인 전사들이 주력으로 편성되었다.

- "허리"(요부), 잠복조 는 승세를 이용하는 것이나 다른 곳에 보강하는 것에 사용되었다. 종종 이들은 숙련된 전사들이 있었다. 이들은 주로 뒤쪽에 배치되었는데, 지나치게 흥분하지 않고 싸우도록 하였다.

포위형 전술은 역사와 전쟁에서 자주 보이는 전술이지만, 중요한 것은 알려지지 않은 적들에게조차 둘러싸며 의례적으로 전투하려고 시도한 것이었다. 더 이전의 예비역 사용과 마찬가지로 별도의 기동요소의 사용은 전 기계화 시대의 부족 전쟁에서 더 강한 중앙 집단을 지원하기 위해 사용되었다고도 잘 알려져 있다. 줄루의 특이한 점은 조직력 정도와, 이러한 전술과 일관성이 있다는 것, 그리고 이들이 이러한 전술을 사용하는 속도였다. 1879년 줄루족이 대영제국에 대항하여 대규모의 연대집단을 사용하다가 목격된 샤카의 죽음 직후, 장비의 발전과 정비가 이루어졌을것이다. 임무, 가용 인력과 적은 다양했지만, 토속 창이나 유럽식 탄환에 맞닥뜨려도, 임피들은 일반적으로 고전적인 황소의 뿔 패턴을 고수했다.

Organisation and leadership of the Zulu forces[편집]

Regiments and corps. The Zulu forces were generally grouped into three levels: regiments, corps of several regiments, and "armies" or bigger formations, although the Zulu did not use these terms in the modern sense. Although size distinctions were taken account of, any grouping of men on a mission could collectively be called an impi, whether a raiding party of 100 or horde of 10,000. Numbers were not uniform but dependent on a variety of factors, including assignments by the king, or the manpower mustered by various clan chiefs or localities. A regiment might be 400 or 4000 men. These were grouped into corps that took their name from the military kraals where they were mustered, or sometimes the dominant regiment of that locality. There were 4 basic ranks: herdboy assistants, warriors, inDunas and higher ranked supremos for a particular mission.

Higher command and unit leadership. Leadership was not a complicated affair. An inDuna guided each regiment, and he in turn answered to senior izinduna who controlled the corps grouping. Overall guidance of the host was furnished by elder izinduna usually with many years of experience. One or more of these elder chiefs might accompany a big force on an important mission, but there was no single "field marshal" in supreme command of all Zulu forces. Regimental izinduna, like the non-coms of today's army, and yesterday's Roman Centurions, were extremely important to morale and discipline. This was shown during the battle of Isandhlwana. Blanketed by a hail of British bullets, rockets and artillery, the advance of the Zulu faltered. Echoing from the mountain, however, were the shouted cadences and fiery exhortations of their regimental izinduna, who reminded the warriors that their king did not send them to run away. Thus encouraged, the encircling regiments remained in place, maintaining continual pressure, until weakened British dispositions enabled the host to make a final surge forward. (See Morris ref below—"The Washing of the Spears").

Summary of the Shakan reforms[편집]

As noted above, Shaka was neither the originator of the impi, or the age grade structure, nor the concept of a bigger grouping than the small clan system. His major innovations were to blend these traditional elements in a new way, to systematise the approach to battle, and to standardise organization, methods and weapons, particularly in his adoption of the ilkwa – the Zulu thrusting spear, unique long-term regimental units, and the "buffalo horns" formation. Dingswayo's approach was of a loose federation of allies under his hegemony, combining to fight, each with their own contingents, under their own leaders. Shaka dispensed with this, insisting instead on a standardised organisation and weapons package that swept away and replaced old clan allegiances with loyalty to himself. This uniform approach also encouraged the loyalty and identification of warriors with their own distinctive military regiments. In time, these warriors, from many conquered tribes and clans came to regard themselves as one nation- the Zulu. The Marian reforms of Rome in the military sphere are referenced by some writers as similar. While other ancient powers such as the Carthaginians maintained a patchwork of force types, and the legions retained such phalanx-style holdovers like the triarii, Marius implemented one consistent standardised approach for all the infantry. This enabled more disciplined formations and efficient execution of tactics over time against a variety of enemies. As one military historian notes:

- Combined with Shaka's "buffalo horns" attack formation for surrounding and annihilating enemy forces, the Zulu combination of iklwa and shield—similar to the Roman legionaries' use of gladius and scutum—was devastating. By the time of Shaka's assassination in 1828, it had made the Zulu kingdom the greatest power in southern Africa and a force to be reckoned with, even against Britain's modern army in 1879.[5]

The Impi in battle[편집]

The impi, in its Shakan form, is best known among Western readers from the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, particularly the famous Zulu victory at Isandhlwana, but its development was over 60 years in coming before that great clash. To understand the full scope of the impi's performance in battle, military historians of the Zulu typically look to its early operations against internal African enemies, not merely the British interlude.[6] In terms of numbers, the operations of the impi would change- from the Western equivalent of small company and battalion size forces, to manoeuvres in multi-divisional strength of between 10,000 and 40,000 men. The victory won by Zulu king Cetawasyo at Ndondakusuka, for example, two decades before the British invasion involved a deployment of 30,000 troops.[7] These were sizeable formations in regional context but represented the bulk of prime Zulu fighting strength. Few impi-style formations were to routinely achieve this level of mobilisation for a single battle. For example, at Cannae, the Romans deployed 80,000 men, and generally could put tens of thousands more into smaller combat actions[8]). The popular notion of countless attacking black spearmen is a distorted one. Manpower supplies on the continent were often limited. In the words of one historian: "The savage hordes of popular lore seldom materialized on African battlefields."[9] This limited resource base would hurt the Zulu when they confronted technologically advanced world powers such as Britain. The advent of new weapons like firearms would also have a profound impact on the African battlefield, but as will be seen, the impi-style forces largely eschewed firearms, or used them in a minor way. Whether facing native spear or European bullet, impis largely fought as they had since the days of Shaka, from Zululand to Zimbabwe, and from Mozambique to Tanzania.[10]

The starting period: Clash at Gqokli Hill[편집]

Upon his accession to power, Shaka was confronted by two potent threats, the Ndwandwes under Zwide, and the Qwabes. Both clans were twice as large as the Zulu. The first key test of the "new model" Shakan impis would be against the Ndwandwe, and the battle offers insight into both Shaka as a commander and the performance of his reorganised combat team. The Zulu king deployed his troops in a strong position on top of Gqokli Hill, using a deep depression on the summit to hide a large central reserve, while grouping his other warriors forward in defensive formation. Shaka also made a decoy gambit -- sending the Zulu cattle off with a small escort, luring Zwide into splitting his force. The battle began in the early morning as the Ndwandwe, under Zwide's son Nomahlanjana, made a series of frontal attacks up the steep hill. Slowed by the incline, and armed only with traditional throwing spears, they were badly mauled by Shaka's men in close quarters fighting. By mid-afternoon, the Ndwandwe were exhausted and their force weakened further by small groups of men going off in search of water. Shaka however had cunningly positioned himself so that his troops had access to a small stream nearby. In the late afternoon the Ndwandwe made a final attack. Leaving a part of their army surrounding the bottom of the hill, they pushed a huge column up to the top, hoping to drive the Zulu down into the blocking forces below. Shaka waited until the column was almost at the top, then ordered his fresh reserves to make a flanking "horn" attack, sprinting down both sides of the hill to encircle and liquidate the ascending Ndwandwe. The rest of the enemy force, which could not clearly see what was happening on the summit was next attacked in another encircling manoeuvre that sent it fleeing. In its first major battle, the Shakan impi had pulled off a multiple envelopment.[11] On the negative side, the Ndwandwe remnants had been able to withdraw intact, and all the Zulu cattle were captured. Shaka furthermore was forced eventually to recall and pull back the warriors to his kraal at kwaBulawayo. Nevertheless, the impi had badly beaten an enemy force over twice its size, killing 5 of Zwide's sons in the process and succeeding in its first major test. A period of rebuilding now commenced and new recruits, either by conquest or alliance were incorporated into the growing Shakan force. Among the newcomers was one Mzilikazi, a small-time chieftain of the Kumalo, and a grandson of Zwide whose father had been killed by Zwide. Mzilikazi would eventually fall out with Shaka, and in fleeing, would extend the concept of the impi even further across the landscape of southern and eastern Africa.[11]

줄루 임피와 그의 파생된 집단의 병합기[편집]

이 시기 샤카의 권력은 성장하며 몇몇 강력한 경쟁자들을 물리쳤고, 해당 지역에서 가장 강력한 국가였던 것을 기념하는 거대한 기념비를 세웠다.

샤카의 성공은 임피와 같은 형태의 다양한 분파들을 나타나게 하였다. 이들 중 우두머리는 므질카지(Mzilkhazi) 휘하의 마테벨레(Matebele)와 경외할 만한 쇼샹가네(Soshangane) 휘하의 샹아안(Shangaan)이었다. [12] 줄루랜드(Zululand)/짐바브웨 지역 외곽에서 임피의 가장 크게 확장된 것은 이들이 동아프리카에 진입한 뒤 샤카가 처음 도입한 방법을 사용하여 응고니족의 전사들이 넓은 영토를 정복했던 때였다.[10]

The first challenge of Europe: African impi versus the Boer Commando[편집]

The impi clashed with another tactical system introduced by European settlers: the horse-gun system of the Boer Commando. This conflict is often popularly conceived of in terms of the well known battles between Zulu King Dingane and the Boers, most notably at the Battle of Blood River. As will be seen however, this tells only part of the story. The impi was to clash with the mobile commando on the open fields of the high veldt in a series of epic confrontations, in which each force both suffered defeat and enjoyed victory, and both sides acquitted themselves well.[13]

The second challenge of Europe: African impi versus the British Empire[편집]

Nearly 35,000 strong,[15] well motivated and supremely confident, the Zulu were a formidable force on their own home ground, despite the almost total lack of modern weaponry. Their greatest assets were their morale, unit leadership, mobility and numbers. Tactically the Zulu acquitted themselves well in at least 3 encounters, Isandhlwana, Hlobane and the smaller Intombi action. Their stealthy approach march, camouflage and noise discipline at Isandhlwana, while not perfect, put them within excellent striking distance of their opponents, where they were able to exploit weaknesses in the camp layout. At Hlobane they caught a British column on the move rather than in the usual fortified position, partially cutting off its retreat and forcing it to withdraw.[16]

Strategically (and perhaps understandably in their own traditional tribal context) they lacked any clear vision of fighting their most challenging war, aside from smashing the three British columns by the weight and speed of their regiments. Despite the Isandhlwana victory, tactically there were major problems as well. They rigidly and predictably applied their three-pronged "buffalo horns" attack, paradoxically their greatest strength, but also their greatest weakness when facing concentrated firepower. The Zulu failed to make use of their superior mobility by attacking the British rear area such as Natal or in interdicting vulnerable British supply lines. However, an important consideration, which King Cetshwayo appreciated, was that there was a clear difference between defending one's territory, and encroaching on another, regardless of the fact that they are at war with the holder of that land. The King realised that peace would be impossible if a real invasion of Natal was launched, and that it would only provoke a more concerted effort on the part of the British against them. The attack on Rorke's Drift, in Natal, was an opportunist raid, as opposed to a real invasion. When they did, they achieved some success, such as the liquidation of a supply detachment at the Intombi River. A more expansive mobile strategy might have cut British communications and brought their lumbering advance to a halt, bottling up the redcoats in scattered strongpoints while the impis ran rampant between them. Just such a scenario developed with the No. 1 British column, which was penned up static and immobile in garrison for over two months at Eshowe.[16]

The Zulu also allowed their opponents too much time to set up fortified strongpoints, assaulting well defended camps and positions with painful losses. A policy of attacking the redcoats while they were strung out on the move, or crossing difficult obstacles like rivers, might have yielded more satisfactory results. For example, four miles past the Ineyzane River, after the British had comfortably crossed, and after they had spent a day consolidating their advance, the Zulu finally launched a typical "buffalo horn" encirclement attack that was seen off with withering fire from not only breech-loading Martini-Henry rifles, but 7-pounder artillery and Gatling guns. In fairness, the Zulu commanders could not conjure regiments out of thin air at the optimum time and place. They too needed time to marshal, supply and position their forces, and sort out final assignments to the three-prongs of attack. Still, the Battle of Hlobane Mountain offers just a glimpse of an alternative mobile scenario, where the manoeuvering Zulu "horns" cut off and drove back Buller's column when it was dangerously strung out on the mountain.[16]

Command and control[편집]

Command and control of the impis was problematic at times. Indeed, the Zulu attacks on the British strongpoints at Rorke's Drift and at Kambula, (both bloody defeats) seemed to have been carried out by over-enthusiastic leaders and warriors despite contrary orders of the Zulu King, Cetshwayo. Popular film re-enactments display a grizzled izinduna directing the host from a promontory with elegant sweeps of the hand. This might have happened during the initial marshaling of forces from a jump off point, or the deployment of reserves, but once the great encircling sweep of frenzied warriors in the "horns" and "chest" was in motion, the izinduna could not generally exercise detailed control.

Handling of reserve forces[편집]

Although the "loins" or reserves were on hand to theoretically correct or adjust an unfavorable situation, a shattered attack could make the reserves irrelevant. Against the Boers at Blood River, massed gunfire broke the back of the Zulu assault, and the Boers were later able to mount a cavalry sweep in counterattack that became a turkey shoot against fleeing Zulu remnants. Perhaps the Zulu threw everything forward and had little left. In similar manner, after exhausting themselves against British firepower at Kambula and Ulindi, few of the Zulu reserves were available to do anything constructive, although the tribal warriors still remained dangerous at the guerrilla level when scattered. At Isandhlwana however, the "classical" Zulu system struck gold, and after liquidating the British position, it was a relatively fresh reserve force that swept down on Rorke's Drift.[17]

Use of Modern Arms and a Missed Opportunity[편집]

The Zulu had greater numbers than their opponents, but greater numbers massed together in compact arrays simply presented easy targets in the age of modern firearms and artillery. African tribes that fought in smaller guerrilla detachments typically held out against European invaders for a much longer time, as witnessed by the 7-year resistance of the Lobi against the French in West Africa,[18] or the operations of the Berbers in Algeria against the French.[19]

When the Zulu did acquire firearms, most notably captured stocks after the great victory at Isandhlwana, they lacked training and used them ineffectively, consistently firing high to give the bullets "strength." Southern Africa, including the areas near Natal, was teeming with bands like the Griquas who had learned to use guns. Indeed, one such group not only mastered the way of the gun, but became proficient horsemen as well, skills that helped build the Basotho tribe, in what is now the nation of Lesotho. In addition, numerous European renegades or adventurers (both Boer and non-Boer) skilled in firearms were known to the Zulu. Some had even led detachments for the Zulu kings on military missions.

The Zulu thus had clear scope and opportunity to master and adapt the new weaponry. They also had already experienced defeat against the Boers, by concentrated firearms. They had had at least four decades to adjust their tactics to this new threat. A well-drilled corps of gunmen or grenadiers, or a battery of artillery operated by European mercenaries for example, might have provided much needed covering fire as the regiments manoeuvred into position.

No such adjustments were on hand when they faced the redcoats. Immensely proud of their system, and failing to learn from their earlier defeats, they persisted in "human wave" attacks against well defended European positions where massed firepower devastated their ranks. The ministrations of an isAngoma (plural: izAngoma) Zulu diviner or "witch doctor", and the bravery of individual regiments were ultimately of little use against the volleys of modern rifles, Gatling guns and artillery at the Ineyzane River, Rorke's Drift, Kambula, Gingingdlovu and finally Ulindi.

A tough challenge[편집]

Undoubtedly, Cetshwayo and his war leaders faced a tough and extremely daunting task – overcoming the challenge of concentrated rifle, Gatling gun, and artillery fire on the battlefield. It was one that also taxed European military leaders, as the carnage of the American Civil War and the later Boer War attests. Nevertheless, Shaka's successors could argue that within the context of their experience and knowledge, they had done the best they could, following his classical template, which had advanced the Zulu from a small, obscure tribe to a respectable regional power known for its fierce warriors.

Demise of the Impi[편집]

The demise of the impi finally came about with the success of European colonisation of Africa- first in southern Africa by the British, and finally in German East Africa as German colonialists defeated the last of the impi-style formations under Mkwawa, chief of the Hehe of Tanzania. The Boers, another major challenger to the impi, also saw defeat by imperial forces, in the Boer War of 1902. In its relatively brief history, the impi inspired both scorn (During the Anglo-Zulu War, British commander Lord Chelmsford complained that they did not 'fight fair') and admiration in its opponents, epitomised in Kipling's poem "Fuzzy Wuzzy":

- We took our chanst among the Khyber 'ills,

- The Boers knocked us silly at a mile,

- The Burman give us Irriwady Chills,

- 'An' a Zulu Impi dished us up in style.

Today the impi lives on in popular lore and culture, even in the West. While the term "impi" has become synonymous with the Zulu nation in international popular culture, it appears in various video games such as Civilization III, Civilization IV: Warlords, Civilization: Revolution, Civilization V: Brave New World, and Civilization VI, where the Impi is the unique unit for the Zulu faction with Shaka as their leader. 'Impi' is also the title of a very famous South Africa song by Johnny Clegg and the band Juluka which has become something of an unofficial national anthem, especially at major international sports events and especially when the opponent is England.

Lyrics:

- Impi! O nans'impi iyeza (Impi! Oh here comes impi)

- Uban'obengathint'amabhubesi? (Who would have touched the lions?)

Before stage seven of the 2013 Tour de France, the Orica-GreenEDGE cycling team played 'Impi' on their team bus in honor of teammate Daryl Impey, the first South African Tour de France leader.[20]

같이 보기[편집]

- 1800년까지의 아프리카 군사 체계

- 1900년 이후의 아프리카 군사 체계

- 아프리카의 군사사

- 아샨티 제국

- 말리 제국

- 말리 제국의 군사사

- 은동고 왕국

- 마탐바 왕국

- 콩고 왕국

- 은동고의 은징가와 마탐바

- 음빌라 전투

- 자마 전투

- 이산들와나 전투

각주[편집]

- ↑ Donald Morris, 'The Washing of the Spears,' Touchstone, 1965.

- ↑ Donald Morris, The Washing of the Spears. p. 32-67

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Morris, 32–67

- ↑ Morris, Washing of the Spears, p. 51.

- ↑ Guttman, Jon. Military History, Jun2008, Vol. 24 Issue 4, p. 23-23.

- ↑ Knight, Ian (1995) Anatomy of the Zulu Army, pp. 3–49.

- ↑ Morris, pp. 195–196

- ↑ Davis, Paul K. (2001), 100 Decisive Battles: From Ancient Times to the Present, pp. 14–126.

- ↑ Bruce Vandervort, Wars of Imperial Conquest in Africa: 1830–1914, Indiana University Press: 1998, p. 39.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 J.D. Omer-Cooper, The Zulu Aftermath.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Morris, Washing of the Spears, pp. 60–69

- ↑ J.D. Omer-Cooper, The Zulu aftermath.

- ↑ See J. D. Omer-Cooper: The Zulu Aftermath and Donald Morris: The Washing of the Spears.

- ↑ Isandlwana 1879: The Great Zulu Victory, by Ian Knight, Osprey: 2002, pp. 49, See also Donald Morris, The Washing of The Spears, Touchstone: 1965, pp. 263-382.

- ↑ Colenso, 1880, p.318, gives the total strength of the Zulu army at 35,000.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 D. Morris-Washing of the Spears- 1965, pp. 263-382

- ↑ I. Knigh. Isandlwana , 2002, p. 49; D. Morri, Washing of the Spears, 1965, pp. 263-382.

- ↑ 스크립트 오류: "citation/CS1" 모듈이 없습니다.

- ↑ 스크립트 오류: "citation/CS1" 모듈이 없습니다.

- ↑ 스크립트 오류: "citation/CS1" 모듈이 없습니다.

This article "임피 (군사)" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical and/or the page Edithistory:임피 (군사). Articles copied from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be seen on the Draft Namespace of Wikipedia and not main one.

|

This page exists already on Wikipedia. |